Federal Civil Asset Forfeiture

If federal or state law enforcement officers are attempting to use asset forfeiture laws to take your property, then contact forfeiture attorney Sebastian Rucci. He has 27 years of legal experience and is very experienced in fighting asset forfeiture cases throughout the United States.

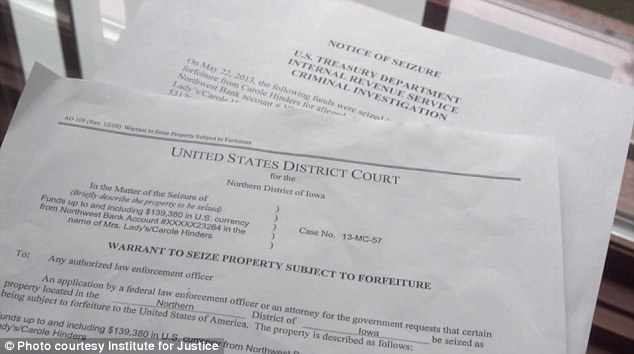

The federal law governing civil in rem forfeiture actions gives the government authority to seize property allegedly used in furtherance of criminal activity and to commence civil in rem proceedings against the property without charging the property’s owner with a crime.

In many of these cases, the government will allege that the currency was forfeitable pursuant to 21 U.S.C. § 881(a)(6), as proceeds traceable to drug trafficking activities or that the property was used or intended to be used to facilitate drug-trafficking in violation of 21 U.S.C. §§ 841(a), 846.

In civil asset forfeiture cases, the United States is the plaintiff who has seized the property. The property or asset itself is named as the defendant. The claimant is the party seeking to intervene in order to get the property back.

Federal agencies with forfeiture authority in the United States include the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives; Drug Enforcement Administration; Federal Bureau of Investigation; Internal Revenue Service; United States Attorney’s Office; U.S. Customs and Border Protection; U.S. Postal Inspection Service; and U.S. Secret Service.

At the pleading stage, the claimant will satisfy the burden of establishing constitutional standing by alleging a sufficient interest in the seized property. That interest can include an ownership interest, lawful possessory interest, or sufficient security interest. To fight the complaint for forfeiture, the claimant can file a motion to dismiss if the Assistant United States Attorney (AUSA) missed a deadline or failed to comply with the strict requirements of CAFRA.

Affirmative defenses include a showing that the money was not the proceeds of illegal drug activity, the claimant is an innocent owner, or the forfeiture constitutes an excessive fine under the Eighth Amendment.

Administrative asset forfeiture refers to “the process by which property may be forfeited by a seizing agency rather than through a judicial proceeding.” 18 U.S.C. § 983. Once the administrative proceeding begins, a claimant may contest the forfeiture by filing a claim, pursuant to the requirements outlined in 18 U.S.C. § 983(a)(2)(C). See 18 U.S.C. § 1983(a)(2). When a claimant files a claim, the asset forfeiture action is converted into a judicial proceeding, and the United States must, within ninety days, file a complaint in accordance with the supplemental rules. See 18 U.S.C. § 1983(3).

Representing the “Innocent Owner” in a Forfeiture Action

An attorney can help you assert the affirmative defense of innocent ownership. The federal civil asset forfeiture statutes are intended to punish drug dealers while still protecting unwitting or innocent owners. Under 21 U.S.C. § 881(a)(6), the statutory scheme differentiates between “wrongdoers” and “innocent owners.”

Any person connected with the property subject to forfeiture is a wrongdoer except those who are innocent owners. Innocent owners are those who have no knowledge of the illegal activities and who have not consented to the illegal activities.

As to a wrongdoer, any amount of the invested proceeds traceable to drug activities forfeits the entire property. In other words, if one is a wrongdoer, the full value of the real property is forfeitable because some of the funds invested are traceable. On the other hand, if a person is an innocent owner, then no amount of that person’s or entity’s funds are forfeitable.

When the innocent owner’s defense is asserted, the burden is on the claimant. In fact, the government need not prove, and the district court need not find, that the claimant had actual knowledge. Instead, it is the claimant’s responsibility to prove the absence of actual knowledge.

The innocent owner’s defense is based on actual knowledge, not constructive knowledge, that existed at the time of the transfer and not at the time of the illegal activity. See United States v. 6640 SW 48th St., 41 F.3d 1448, 1452 (11th Cir.1995).

This rule prohibits profit by the post-illegal act transferees who knowingly take an interest in the forfeitable property. The innocent owner’s defense is not available just because the person was not on the scene early enough to consent to the illegal activity.

In other words, the post-illegal act transferee cannot assert the innocent owner’s defense to forfeiture if he could know of the illegal activity which would subject property to forfeiture at the time he takes his interest. When considering the innocent owner’s defense, the courts are looking to see if a “strawman” setup is being used to conceal the financial affairs of illegal dealings of someone else.

Challenges to Forfeiture under the Eighth Amendment’s Excessive Fine Clause

In many of these cases, the attorney will raise an affirmative defense alleging that the forfeiture was excessive under the “excessive fine clause” of the Eighth Amendment. The constitutional challenge to forfeiture on this basis should be raised at the first opportunity and renewed at each stage of the case.

In United States v. Bajakajian, the Supreme Court of the United States established a two-step inquiry to determine whether the forfeiture was excessive under the Eighth Amendment. 524 U.S. 321 (1998). The first step involves determining whether the Excessive Fines Clause applies to the forfeiture. The Excessive Fines Clause applies only where the forfeiture may be characterized, at least in part, as punitive. The second step involves determining whether the challenged forfeiture is unconstitutionally excessive. A forfeiture is unconstitutionally excessive “if it is grossly disproportional to the gravity of a defendant’s offense.” Bajakajian, 524 U.S. at 334.

The federal courts have not developed a bright-line test for determining gross disproportionality, but the courts have interpreted the Bajakajian decision as requiring the courts to consider the following four factors: the essence of the crime of the defendant and its relation to other criminal activity; whether the defendant fits into the class of persons for whom the statute was principally designed; the maximum sentence and fine that could have been imposed; and the nature of the harm caused by the defendant’s conduct. United States v. Viloski, 814 F.3d 104, 110 (2d Cir. 2016). The claimant can also file a motion to dismiss based on the five (5) year statute of limitations for civil asset forfeiture cases.

List of Defenses in a Federal Civil Asset Forfeiture Case

The Assistant United States Attorney (AUSA) working as an Asset Forfeiture Coordinator o Financial Litigation Coordinator at the U.S. Attorney’s Office makes the decision about whether to file a complaint for forfeiture against the seized property. If the AUSA files a complaint for forfeiture, anyone asserting a claim to that property must file an answer and assert the following affirmative defenses. If the AUSA misses that 90-day deadline to file the complaint, the claimant can file a claim for violations of the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”), a claim for violation of CAFRA, a Fifth Amendment claim, a Fourth Amendment claim, a claim for mandamus, or a claim under the Federal Tort Claims Act (“FTCA”) for replevin and conversion.

-

- Other defenses to the complaint for forfeiture might include:

-

- Plaintiff’s complaint fails to state claims upon which relief may be granted.

-

- The forfeiture violates the excessive fines clause of the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

-

- The seizure was in violation of Defendant’s Fourth Amendment right to be free from an unreasonable seizure without probable cause.

-

- There was no substantial connection between the Defendant’s property and an offense as required by 18 U.S.C. § 983(c)(3).

-

- The Defendant’s right to due process was violated by the government for failing to follow the strict time limits for the initiation of a forfeiture.

-

- The federal government failed to follow proper procedures and violated Defendant’s due process rights by taking property originally seized by state and federal officers.

-

- 21 U.S.C. § 881 is unconstitutional because the government is attempting to punish the Claimant for a crime without a grand jury indictment and without the safeguards of Due Process as afforded by the United States Constitution.

-

- The property is not subject to seizure and forfeiture

-

- There is no probable cause to believe that the Defendant Property was used or maintained, or intended to be used or maintained, to commit or to facilitate the commission of any violation of 21 U.S.C. §§ 841 or 846.

-

- The federal government is estopped from obtaining a forfeiture judgment because the seizure warrant was obtained through incorrect, misleading, or incomplete allegations.

-

- The federal government cannot obtain a forfeiture judgment because it has not acted in good faith.

-

- The equitable sharing provisions of the federal forfeiture program, including Titles 21 U.S.C.§ 881(e)(1)(A) and (e)(3); 18 U.S.C. § 981(e)(2); 18 U.S.C. § 1963(g); and 19 U.S.C. § 1616(a), exceed the lawful powers of the federal government.

-

- These provisions create a means and an incentive for local law enforcement agencies to unilaterally circumvent state forfeiture laws, resulting in an actual, concrete injury to Claimants.

-

- The provisions deprive the people of knowingly accepting participation in the equitable sharing program, and thereby impair state sovereignty and commandeer state and local law enforcement agencies to administer federal laws contrary to state policy in violation of the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

-

- The federal government did not provide the Claimant with proper notice of the seizure in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 983(a).

-

- None of the Claimant’s conduct or activities affect interstate commerce.

-

- The proceeds are not from unlawful activity.

-

- The claim is barred by the prohibition of depriving citizens of property without due process of law as provided for in the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

-

- The Government has waited an unduly long time in asserting its claims and such delay has prejudiced the Claimant’s rights and hindered the ability to defend/respond in this case, therefore, the Plaintiff’s claims are barred by Laches.

-

- Plaintiff has waived any claims it may otherwise have had.

-

- Plaintiff’s Complaint does not comply with the requirement of Supplemental Rule G to “state sufficiently detailed facts to support a reasonable belief that the government will be able to meet its burden of proof at trial.”

-

- Forfeiture of the Defendant’s currency is barred by the Appropriations Clause of Article 1, Section 9 of the United States Constitution.

-

- If the forfeiture is completed, law enforcement agencies will be able to use money from the forfeiture to fund their activities absent any appropriation from Congress. But, under the Appropriations Clause, money for government spending must be secured through congressional appropriation.

The attorney defending the civil asset forfeiture action by answering the complaint will often demand a trial by jury on all issues so triable. Additionally, the answer to the complaint will request: that the Court deny Plaintiff’s claim for forfeiture of the Defendant’s currency; that the Court order the Defendant’s currency or other property returned to the Claimant; that the Court order that Plaintiff pay Claimant’s attorney’s fees and costs pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §2465(b)(1)(A); that the Court order that the U.S. Government pay pre-and post-judgment interest on the Defendant currency to Claimant pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §2465(b)(1)(B)-(C); and such additional relief as the Court deems just and proper.

Motions in Civil Asset Forfeiture Cases

In civil forfeiture actions at the federal level, the attorney for the claimant should consider the available motions that can be filed under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure including all of the Rule 12 Motions to Dismiss. Under federal law, the discovery tools and motions used in these cases include Interrogatories — Sworn answers to written questions – Rule 33; Depositions — Sworn oral testimony under oath – Rules 30-31; Document requests — Requests for specific categories of documents – Rule 34; Motion to Compel – Fed. R. Civ. P. 36(a); and Motion for Summary Judgment.- Fed. R. Civ. P. 56.

In civil asset forfeiture cases, a motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim can be filed under Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6). The pleading requirements are found in Supplemental Rule G(2). The motion tests the sufficiency of the allegations in the complaint. The government must state a claim with enough detail to show it can meet its burden of proof at trial. Because the government is holding property from the beginning, the law requires more particularity than in a standard non-fraud civil complaint.

Attorney Sebastian Rucci Focuses His Law Practice on Seizures and Asset Forfeitures

Forfeiture Attorney Sebastian Rucci has 27 years of legal experience and FOCUSES HIS PRACTICE ON SEIZURES AND ASSET FORFEITURES. He also works with other attorneys co-counsel on civil asset forfeiture cases.

Forfeiture attorney Sebastian Rucci will challenge federal asset forfeiture cases throughout the United States. He can file a verified claim for the seized assets, an answer challenging the allegations in the verified forfeiture complaint, seek an adversarial preliminary hearing if one was denied, and challenge the seizure by filing a motion to suppress and dismiss on multiple procedural grounds demanding the immediate return of the seized assets.

Forfeiture attorney Sebastian Rucci can show that the seized assets are not the proceeds of criminal activity and that the agency did not have probable cause to seize the funds or other assets. Even if a showing of probable cause has been made, he can file to rebut the probable cause by demonstrating that the forfeiture statute was not violated, that the agency failed to trace the funds, or showing an affirmative defense that entitles the immediate return of the seized assets.

Forfeiture attorney Sebastian Rucci is available as co-counsel, working with other counsel, where he focuses on challenging the asset forfeiture and seizure aspect of the case throughout the United States. Forfeiture attorney Sebastian Rucci often takes civil asset forfeiture cases on a contingency fee basis, which means that you pay nothing until the money or other asset is returned. Let experienced forfeiture attorney Sebastian Rucci put his experience with federal seizures and forfeiture actions to work for you, call attorney Sebastian Rucci at 330-720-0398.

Newspaper Articles About Forfeiture Abuses

LA TIMES (9-23-2022): FBI misled the Judge on Beverly Hills safe deposit box seizure

CNBC (10-20-22): Customers battle to regain billions in bitcoin seized by DOJ

CNBC (10-20-22): Customers battle to regain billions in bitcoin seized by DOJ

USA Today (7-16-2021): Innocent people shouldn’t lose cash to forfeiture

LA TIMES (5-10-2022): FBI gives up attempt to confiscate $1 million

CNN (1-31-2022): FBI illegally seized cash belonging to licensed dispensaries

Attorney for Federal Civil Asset Forfeiture

After the government commences a civil forfeiture action, you should act quickly to retain an attorney to file a claim asserting your property ownership claim. We can help you properly file a verified claim with the seizing agency under 18 U.S.C. § 983(a)(2).

If a complaint for forfeiture is filed, we can help you file a verified claim under Rule C(6) which is distinct and separate from filing an administrative claim. In addition to filing the verified claim under Rule C(6), we can help you file the answer, motion to dismiss, motion to suppress, and demand for attorney fees and costs.

Forfeiture attorney Sebastian Rucci can help you assert affirmative defenses including a showing that the money was not the proceeds of illegal drug activity or bulk cash smuggling. He can also represent an innocent owner who was not present when the money was seized. If the government’s action is barred by the five (5) year statute of limitations, he can file a motion to dismiss the forfeiture action. Whether your cash was seized at the airport or taken in connection with a criminal prosecution, forfeiture attorney Sebastian Rucci can help.

Don’t waive any of your rights by pursuing administrative options through a petition for remission or mitigation until you speak with forfeiture attorney Sebastian Rucci. The best course of action is to demand early judicial intervention in the U.S. District Court immediately after the seizure.

Experienced asset forfeiture attorney Sebastian Rucci can challenge federal asset forfeiture cases throughout the United States. He can help you file a verified claim for the seized asset, an answer challenging the allegations in the verified forfeiture complaint, they can demand an adversarial preliminary hearing if one was denied, challenge an illegal search or seizure to suppress and return the seized finds and file to dismiss the forfeiture complaint on various other procedural grounds and seek the immediate return of the seized assets.

Experienced asset forfeiture attorney Sebastian Rucci can help you show that the seized funds, or other assets, are not the proceeds of criminal activity and that the agency did not have probable cause to seize the funds or file the forfeiture action. Even if a showing of probable cause has been made, experienced asset forfeiture attorneys can help you meet the burden of rebutting the probable cause showing, demonstrating why the forfeiture statute was not violated, or showing an affirmative defense that entitles the claimant to repossession of the seized assets.

Experienced asset forfeiture attorney Sebastian Rucci often takes civil asset forfeiture cases on a contingency fee basis, you pay nothing until the money or other asset is returned. He often works with attorneys in other jurisdictions as co-counsel to fight these cases throughout the United States.

The Government’s Notice Obligations in a Civil Asset Forfeiture Action

Supplemental Rule G “governs a forfeiture action in rem arising from a federal statute.” Supp. R. G(1). To discharge its notice obligations in a civil asset forfeiture action, the United States must provide notice of the action to any potential claimants. See Supp. R. G(4). Supplemental Rule G(4)(a)(i) relates to notice by a publication by stating: “A judgment of forfeiture may be entered only if the government has published notice of the action within a reasonable time after filing the complaint or at a time the court orders.”

As provided in Supp. R. G(4)(a)(ii) the notice must contain the following information: describe the property with reasonable particularity; state the times under Rule G(5) to file a claim and to answer; and name the government attorney to be served with the claim and answer.

Supplemental Rule G(4)(b)(ii) relates to notice to known potential claimants by providing: “The government must send notice of the action and a copy of the complaint to any person who reasonably appears to be a potential claimant on the facts known to the government before the end of the time for filing a claim under Rule G(5)(a)(ii)(B).” Supp. R. G(4)(b).

The notice must state: (i) the date the notice is sent; (ii) “a deadline for filing a claim, at least 35 days after the notice is sent”; (iii) “that an answer or motion under Rule 12 must be filed no later than 21 days after filing the claim”; and (iv) “the name of the government attorney to be served with the claim and answer.”

Intervening in a Civil Asset Forfeiture Action

To intervene in a civil asset forfeiture action, each claimant must meet both Article III and statutory standing requirements. To demonstrate Article III standing, the claimant must have an interest in the property sufficient to create a “case or controversy.”

To establish statutory standing, a claimant must comply with Supplemental Rule G(5)’s pleading requirements. Supplemental Rule G(5) states that to assert their claim in a civil forfeiture action, claimants must file both a verified claim and an answer to the United States’ complaint. See Supp. R. G(5).

Supplemental Rule G(5) requires a claimant to file both a verified claim and an answer. The claim ensures that any party who wishes to defend a forfeiture action will be forced to swear his interest in the forfeited property.

Supplemental Rule G(8)(c) allows the United States to move to strike a claimant’s claim or answer under certain circumstances. See Supp. R. G(8)(c). Supplemental Rule G(8)(c) states: “At any time before trial, the government may move to strike a claim or answer … for failing to comply with Rule G(5) or (6), or … because the claimant lacks standing.” Supp. R. G(8)(c).

The advisory committee notes to Supplemental Rule G(8)(c)(i)(A) state: “As with other pleadings, the court should strike a claim or answer only if satisfied that an opportunity should not be afforded to cure the defects under Rule 15.”

While failure to comply with Supplemental Rule G(5) or G(6) constitutes grounds for a motion to strike a claimant’s claim or answer pursuant to Supplemental Rule G(8)(c), some courts have stated that a court may exercise discretion in extending the time for filing of a verified claim.

Administrative Asset Forfeiture

Administrative asset forfeiture refers to “the process by which property may be forfeited by a seizing agency rather than through a judicial proceeding.” 18 U.S.C. § 983. Once the administrative proceeding begins, a claimant may contest the forfeiture by filing a claim, pursuant to the requirements outlined in 18 U.S.C. § 983(a)(2)(C). See 18 U.S.C. § 1983(a)(2). When a claimant files a claim, the asset forfeiture action is converted into a judicial proceeding, and the United States must, within ninety days, file a complaint in accordance with the supplemental rules. See 18 U.S.C. § 1983(3).

The Government’s Notice Obligations in a Civil Asset Forfeiture Action

Supplemental Rule G “governs a forfeiture action in rem arising from a federal statute.” Supp. R. G(1). To discharge its notice obligations in a civil asset forfeiture action, the United States must provide notice of the action to any potential claimants. See Supp. R. G(4). Supplemental Rule G(4)(a)(i) relates to notice by a publication by stating: “A judgment of forfeiture may be entered only if the government has published notice of the action within a reasonable time after filing the complaint or at a time the court orders.”

As provided in Supp. R. G(4)(a)(ii) the notice must contain the following information: describe the property with reasonable particularity; state the times under Rule G(5) to file a claim and to answer; and name the government attorney to be served with the claim and answer.

Supplemental Rule G(4)(b)(ii) relates to notice to known potential claimants by providing: “The government must send notice of the action and a copy of the complaint to any person who reasonably appears to be a potential claimant on the facts known to the government before the end of the time for filing a claim under Rule G(5)(a)(ii)(B).” Supp. R. G(4)(b).

The notice must state: (i) the date the notice is sent; (ii) “a deadline for filing a claim, at least 35 days after the notice is sent”; (iii) “that an answer or motion under Rule 12 must be filed no later than 21 days after filing the claim”; and (iv) “the name of the government attorney to be served with the claim and answer.”

Intervening in a Civil Asset Forfeiture Action

To intervene in a civil asset forfeiture action, each claimant must meet both Article III and statutory standing requirements. To demonstrate Article III standing, the claimant must have an interest in the property sufficient to create a “case or controversy.”

To establish statutory standing, a claimant must comply with Supplemental Rule G(5)’s pleading requirements. Supplemental Rule G(5) states that to assert their claim in a civil forfeiture action, claimants must file both a verified claim and an answer to the United States’ complaint. See Supp. R. G(5).

Supplemental Rule G(5) requires a claimant to file both a verified claim and an answer. The claim ensures that any party who wishes to defend a forfeiture action will be forced to swear his interest in the forfeited property.

Supplemental Rule G(8)(c) allows the United States to move to strike a claimant’s claim or answer under certain circumstances. See Supp. R. G(8)(c). Supplemental Rule G(8)(c) states: “At any time before trial, the government may move to strike a claim or answer … for failing to comply with Rule G(5) or (6), or … because the claimant lacks standing.” Supp. R. G(8)(c).

The advisory committee notes to Supplemental Rule G(8)(c)(i)(A) state: “As with other pleadings, the court should strike a claim or answer only if satisfied that an opportunity should not be afforded to cure the defects under Rule 15.”

While failure to comply with Supplemental Rule G(5) or G(6) constitutes grounds for a motion to strike a claimant’s claim or answer pursuant to Supplemental Rule G(8)(c), some courts have stated that a court may exercise discretion in extending the time for filing of a verified claim.

Administrative Asset Forfeiture

Administrative asset forfeiture refers to “the process by which property may be forfeited by a seizing agency rather than through a judicial proceeding.” 18 U.S.C. § 983. Once the administrative proceeding begins, a claimant may contest the forfeiture by filing a claim, pursuant to the requirements outlined in 18 U.S.C. § 983(a)(2)(C). See 18 U.S.C. § 1983(a)(2). When a claimant files a claim, the asset forfeiture action is converted into a judicial proceeding, and the United States must, within ninety days, file a complaint in accordance with the supplemental rules. See 18 U.S.C. § 1983(3).

Representing the “Innocent Owner” in a Forfeiture Action

An attorney can help you assert the affirmative defense of innocent ownership. The federal civil asset forfeiture statutes are intended to punish drug dealers while still protecting unwitting or innocent owners. Under 21 U.S.C. § 881(a)(6), the statutory scheme differentiates between “wrongdoers” and “innocent owners.”

Any person connected with the property subject to forfeiture is a wrongdoer except those who are innocent owners. Innocent owners are those who have no knowledge of the illegal activities and who have not consented to the illegal activities.

As to a wrongdoer, any amount of the invested proceeds traceable to drug activities forfeits the entire property. In other words, if one is a wrongdoer, the full value of the real property is forfeitable because some of the funds invested are traceable. On the other hand, if a person is an innocent owner, then no amount of that person’s or entity’s funds are forfeitable.

When the innocent owner’s defense is asserted, the burden is on the claimant. In fact, the government need not prove, and the district court need not find, that the claimant had actual knowledge. Instead, it is the claimant’s responsibility to prove the absence of actual knowledge.

The innocent owner’s defense is based on actual knowledge, not constructive knowledge, that existed at the time of the transfer and not at the time of the illegal activity. See United States v. 6640 SW 48th St., 41 F.3d 1448, 1452 (11th Cir.1995).

This rule prohibits profit by the post-illegal act transferees who knowingly take an interest in the forfeitable property. The innocent owner’s defense is not available just because the person was not on the scene early enough to consent to the illegal activity.

In other words, the post-illegal act transferee cannot assert the innocent owner’s defense to forfeiture if he could know of the illegal activity which would subject property to forfeiture at the time he takes his interest. When considering the innocent owner’s defense, the courts are looking to see if a “strawman” setup is being used to conceal the financial affairs of illegal dealings of someone else.

Challenges to Forfeiture under the Eighth Amendment’s Excessive Fine Clause

In many of these cases, the attorney will raise an affirmative defense alleging that the forfeiture was excessive under the “excessive fine clause” of the Eighth Amendment. The constitutional challenge to forfeiture on this basis should be raised at the first opportunity and renewed at each stage of the case.

In United States v. Bajakajian, the Supreme Court of the United States established a two-step inquiry to determine whether the forfeiture was excessive under the Eighth Amendment. 524 U.S. 321 (1998). The first step involves determining whether the Excessive Fines Clause applies to the forfeiture. The Excessive Fines Clause applies only where the forfeiture may be characterized, at least in part, as punitive. The second step involves determining whether the challenged forfeiture is unconstitutionally excessive. A forfeiture is unconstitutionally excessive “if it is grossly disproportional to the gravity of a defendant’s offense.” Bajakajian, 524 U.S. at 334.

The federal courts have not developed a bright-line test for determining gross disproportionality, but the courts have interpreted the Bajakajian decision as requiring the courts to consider the following four factors: the essence of the crime of the defendant and its relation to other criminal activity; whether the defendant fits into the class of persons for whom the statute was principally designed; the maximum sentence and fine that could have been imposed; and the nature of the harm caused by the defendant’s conduct. United States v. Viloski, 814 F.3d 104, 110 (2d Cir. 2016). The claimant can also file a motion to dismiss based on the five (5) year statute of limitations for civil asset forfeiture cases.

List of Defenses in a Federal Civil Asset Forfeiture Case

The Assistant United States Attorney (AUSA) working as an Asset Forfeiture Coordinator o Financial Litigation Coordinator at the U.S. Attorney’s Office makes the decision about whether to file a complaint for forfeiture against the seized property. If the AUSA files a complaint for forfeiture, anyone asserting a claim to that property must file an answer and assert the following affirmative defenses. If the AUSA misses that 90-day deadline to file the complaint, the claimant can file a claim for violations of the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”), a claim for violation of CAFRA, a Fifth Amendment claim, a Fourth Amendment claim, a claim for mandamus, or a claim under the Federal Tort Claims Act (“FTCA”) for replevin and conversion.

-

- Other defenses to the complaint for forfeiture might include:

-

- Plaintiff’s complaint fails to state claims upon which relief may be granted.

-

- The forfeiture violates the excessive fines clause of the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

-

- The seizure was in violation of Defendant’s Fourth Amendment right to be free from an unreasonable seizure without probable cause.

-

- There was no substantial connection between the Defendant’s property and an offense as required by 18 U.S.C. § 983(c)(3).

-

- The Defendant’s right to due process was violated by the government for failing to follow the strict time limits for the initiation of a forfeiture.

-

- The federal government failed to follow proper procedures and violated Defendant’s due process rights by taking property originally seized by state and federal officers.

-

- 21 U.S.C. § 881 is unconstitutional because the government is attempting to punish the Claimant for a crime without a grand jury indictment and without the safeguards of Due Process as afforded by the United States Constitution.

-

- The property is not subject to seizure and forfeiture

-

- There is no probable cause to believe that the Defendant Property was used or maintained, or intended to be used or maintained, to commit or to facilitate the commission of any violation of 21 U.S.C. §§ 841 or 846.

-

- The federal government is estopped from obtaining a forfeiture judgment because the seizure warrant was obtained through incorrect, misleading, or incomplete allegations.

-

- The federal government cannot obtain a forfeiture judgment because it has not acted in good faith.

-

- The equitable sharing provisions of the federal forfeiture program, including Titles 21 U.S.C.§ 881(e)(1)(A) and (e)(3); 18 U.S.C. § 981(e)(2); 18 U.S.C. § 1963(g); and 19 U.S.C. § 1616(a), exceed the lawful powers of the federal government.

-

- These provisions create a means and an incentive for local law enforcement agencies to unilaterally circumvent state forfeiture laws, resulting in an actual, concrete injury to Claimants.

-

- The provisions deprive the people of knowingly accepting participation in the equitable sharing program, and thereby impair state sovereignty and commandeer state and local law enforcement agencies to administer federal laws contrary to state policy in violation of the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

-

- The federal government did not provide the Claimant with proper notice of the seizure in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 983(a).

-

- None of the Claimant’s conduct or activities affect interstate commerce.

-

- The proceeds are not from unlawful activity.

-

- The claim is barred by the prohibition of depriving citizens of property without due process of law as provided for in the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

-

- The Government has waited an unduly long time in asserting its claims and such delay has prejudiced the Claimant’s rights and hindered the ability to defend/respond in this case, therefore, the Plaintiff’s claims are barred by Laches.

-

- Plaintiff has waived any claims it may otherwise have had.

-

- Plaintiff’s Complaint does not comply with the requirement of Supplemental Rule G to “state sufficiently detailed facts to support a reasonable belief that the government will be able to meet its burden of proof at trial.”

-

- Forfeiture of the Defendant’s currency is barred by the Appropriations Clause of Article 1, Section 9 of the United States Constitution.

-

- If the forfeiture is completed, law enforcement agencies will be able to use money from the forfeiture to fund their activities absent any appropriation from Congress. But, under the Appropriations Clause, money for government spending must be secured through congressional appropriation.

The attorney defending the civil asset forfeiture action by answering the complaint will often demand a trial by jury on all issues so triable. Additionally, the answer to the complaint will request: that the Court deny Plaintiff’s claim for forfeiture of the Defendant’s currency; that the Court order the Defendant’s currency or other property returned to the Claimant; that the Court order that Plaintiff pay Claimant’s attorney’s fees and costs pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §2465(b)(1)(A); that the Court order that the U.S. Government pay pre-and post-judgment interest on the Defendant currency to Claimant pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §2465(b)(1)(B)-(C); and such additional relief as the Court deems just and proper.

Motions in Civil Asset Forfeiture Cases

In civil forfeiture actions at the federal level, the attorney for the claimant should consider the available motions that can be filed under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure including all of the Rule 12 Motions to Dismiss. Under federal law, the discovery tools and motions used in these cases include Interrogatories — Sworn answers to written questions – Rule 33; Depositions — Sworn oral testimony under oath – Rules 30-31; Document requests — Requests for specific categories of documents – Rule 34; Motion to Compel – Fed. R. Civ. P. 36(a); and Motion for Summary Judgment.- Fed. R. Civ. P. 56.

In civil asset forfeiture cases, a motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim can be filed under Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6). The pleading requirements are found in Supplemental Rule G(2). The motion tests the sufficiency of the allegations in the complaint. The government must state a claim with enough detail to show it can meet its burden of proof at trial. Because the government is holding property from the beginning, the law requires more particularity than in a standard non-fraud civil complaint.

Attorney Sebastian Rucci Focuses His Law Practice on Seizures and Asset Forfeitures

Forfeiture Attorney Sebastian Rucci has 27 years of legal experience and FOCUSES HIS PRACTICE ON SEIZURES AND ASSET FORFEITURES. He also works with other attorneys co-counsel on civil asset forfeiture cases.

Forfeiture attorney Sebastian Rucci will challenge federal asset forfeiture cases throughout the United States. He can file a verified claim for the seized assets, an answer challenging the allegations in the verified forfeiture complaint, seek an adversarial preliminary hearing if one was denied, and challenge the seizure by filing a motion to suppress and dismiss on multiple procedural grounds demanding the immediate return of the seized assets.

Forfeiture attorney Sebastian Rucci can show that the seized assets are not the proceeds of criminal activity and that the agency did not have probable cause to seize the funds or other assets. Even if a showing of probable cause has been made, he can file to rebut the probable cause by demonstrating that the forfeiture statute was not violated, that the agency failed to trace the funds, or showing an affirmative defense that entitles the immediate return of the seized assets.

Forfeiture attorney Sebastian Rucci is available as co-counsel, working with other counsel, where he focuses on challenging the asset forfeiture and seizure aspect of the case throughout the United States. Forfeiture attorney Sebastian Rucci often takes civil asset forfeiture cases on a contingency fee basis, which means that you pay nothing until the money or other asset is returned. Let experienced forfeiture attorney Sebastian Rucci put his experience with federal seizures and forfeiture actions to work for you, call attorney Sebastian Rucci at 330-720-0398.