Civil Asset Forfeiture: Where Due Process Goes to Die

Police can take your money or property and keep it, even if no charges are filed.

Clarence Thomas is famously taciturn on the bench. But his few words carry a great deal of weight.

TOP STORIES

Nikki Haley’s Sin Isn’t Racism

The Hard Realities Facing Ron DeSantis

Maine Secretary of State Rules Trump Is Disqualified from 2024 Ballot

Francis Collins’s Covid Confession

A Reckoning for the Rising-Inequality Narrative

The Peace Processors Return

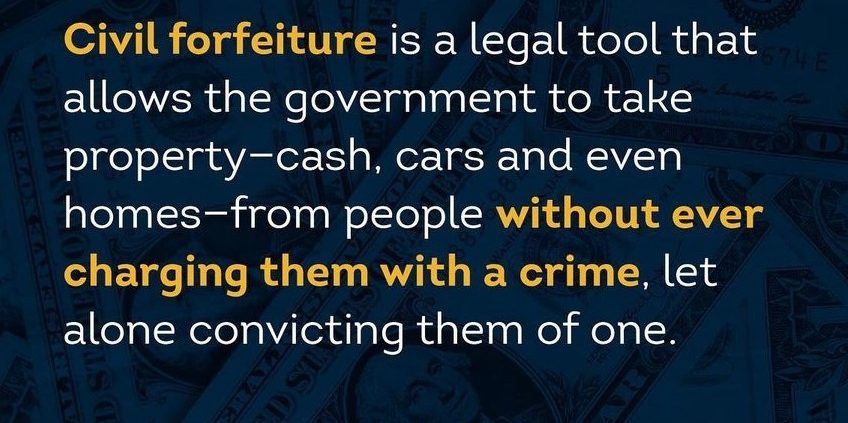

Though the matter has not yet come before the Supreme Court, Justice Thomas is very much at the center of a federal case with a name that sounds like it ought to have come from a William Gaddis novel: United States v. Seventeen Thousand Nine Hundred Dollars in United States Currency. The case has the potential to help rein in one of the most abused powers enjoyed by American government: asset forfeiture.

The case involves a New York couple, Angela Rodriguez and Joyce Copeland, who lost the above-mentioned $17,900 to police in a case in which no charges were ever filed against them. They sued for recovery of their money, and — incredibly — a federal court found that they lacked standing to sue for possession of their own assets. The D.C. Circuit Court sees things differently and has ruled in favor of allowing Rodriguez and Copeland to at least have their day in court and attempt to reclaim their money.

Current asset-forfeiture practice, like much that is wrong with U.S. law enforcement, has its roots in the so-called war on drugs. The practice of seizing assets is ancient: It dates back at least to 17th-century maritime law, under which ships illegally transporting goods would be seized, along with the contraband inside. Asset forfeiture was used against bootleggers during Prohibition, but it really came into its own in the Reagan era, when the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984 empowered federal and local law-enforcement agencies to take property from drug kingpins for their own use. The sudden, unlikely inventory of exotic cars and yachts possessed by law-enforcement agencies inspired that great cultural document of the 1980s: Miami Vice.

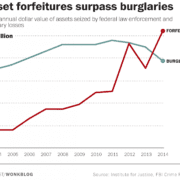

Asset forfeiture creates an obvious conflict of interest for law-enforcement agencies: Because the proceeds go into their budgets, they have a vested interest in maximizing the use of forfeiture in their jurisdictions. You will be less than surprised to learn that this has produced some serious abuses, and the law-enforcement tool intended to be used against centimillionaire cartel bosses inevitably ends up being used to harass — and loot — nobodies in East Funky. That is the nature of such innovations in government. It is why the city won’t fix your potholes but the revenue-producing red-light camera is never on the fritz for long.

(Here’s a prediction: In a fashion similar to that of the weapons in the war on drugs, the tools created for the so-called war on terror are going to present acute problems for Americans in 20 years — far beyond what they already have — as their metastatic spread throughout government continues.)

The spreading use of forfeiture has of course drawn resistance amid concerns about due process and outright abuse. The Supreme Court declined to hear a high-profile forfeiture case, Leonard v. Texas, for procedural reasons. But Justice Thomas issued a statement on the case that was both erudite and blistering. It was also very humane: Justice Thomas has a keen interest in the literary details as well as the legal ones. He wrote:

This system — where police can seize property with limited judicial oversight and retain it for their own use — has led to egregious and well-chronicled abuses. According to one nationally publicized report, for example, police in the town of Tenaha, Texas, regularly seized the property of out-of-town drivers passing through and collaborated with the district attorney to coerce them into signing waivers of their property rights. In one case, local officials threatened to file unsubstantiated felony charges against a Latino driver and his girlfriend and to place their children in foster care unless they signed a waiver. In another, they seized a black plant worker’s car and all his property (including cash he planned to use for dental work), jailed him for a night, forced him to sign away his property, and then released him on the side of the road without a phone or money. He was forced to walk to a Wal-Mart, where he borrowed a stranger’s phone to call his mother, who had to rent a car to pick him up.

These forfeiture operations frequently target the poor and other groups least able to defend their interests in forfeiture proceedings. Perversely, these same groups are often the most burdened by forfeiture. They are more likely to use cash than alternative forms of payment, like credit cards, which may be less susceptible to forfeiture. And they are more likely to suffer in their daily lives while they litigate for the return of a critical item of property, such as a car or a home.

More from

KEVIN D. WILLIAMSON

Steve Bannon’s Gravy Train Gets Derailed

God Save Johnny Rotten

A Clear and Present Danger

The issue, Justice Thomas wrote, is “whether modern civil-forfeiture statutes can be squared with the Due Process Clause and our Nation’s history.” Because these asset-forfeiture proceedings are civil rather than criminal actions, their targets do not enjoy the ordinary procedural protections that they would if they were charged with crimes, the most important of those being jury trials and the heightened standard of evidence demanded in criminal proceedings. Forfeiture cases in effect allow police to punish people for committing crimes without having to go to the trouble of proving that they have committed those crimes. And the fact that the police get to keep the money does not exactly discourage them.

The fact that the practice is a longstanding one does not mean that it is a constitutional one.

The fact that the practice is a longstanding one does not mean that it is a constitutional one. We are not seizing the unflagged vessels of smugglers at colonial ports; and even if we were, it is not clear, as Justice Thomas notes, that those seizures were permitted to advance as purely civil matters unconnected to any underlying criminal charge. Due process does not have a great many friends just now: Congressional Democrats have made a campaign out of revoking the civil rights of Americans put on secret government terrorism watch lists, even if those people have never been charged with, much less convicted of, any actual crime. These episodes are a constant reminder that what conservatives intend to conserve, and what progressives intend to progress away from, is Anglo-American liberalism, with its individual rights, procedural justice, and rule of law.

Leonard wasn’t the case that will be used to sort out forfeiture, but Justice Thomas’s Leonard statement was repeatedly cited in the ruling for the plaintiffs in United States v. Seventeen Thousand Nine Hundred Dollars in United States Currency. Justice Thomas may not say very much on the bench, but he has made it clear that when forfeiture finally does come before the nation’s highest court, at least one gimlet-eyed justice is going to be skeptical.

![shutterstock_120789925_0[1]](https://forfeitureusa.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/shutterstock_120789925_01-180x180.jpg)