For Phelps County: Seizing Suspects’ Assets Is Like ‘Pennies From Heaven’

A newly renovated red-brick jail is nearing completion. Low-milage squad cars patrol the roads. A new high-tech courtroom makes it easier to guard prisoners. Outside the courtroom are exercise equipment and a shoot, no-shoot training facility for officers.

All were funded by the cash and other property the Phelps County Sheriff’s Department has seized in the past decade from motorists traveling along Interstate 44, a major drug corridor passing through the county.

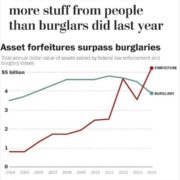

Phelps County deputies seized more than $1 million a year from cars on I-44, according to reports filed with the Missouri State Auditor and obtained by the Sunshine Law. Under the nation’s controversial civil asset-forfeiture laws, police can seize property they think is connected to a crime and later spend the cash on law-enforcement purposes.

Records show Phelps County, like other jurisdictions, almost never files state criminal charges against those whose cash they seize, nor does it make big drug seizures during these stops targeting cash.

Deputies seized more than $2 million in 24 stops along I-44 near Rolla in mid-Missouri between 2016 and 2017. This extends roughly from Dixon, Missouri, and Sugar Tree Road on the west, past Doolittle and Rolla to St. James, Missouri.

No state criminal charges were filed in any of the 24 stops, records show.

Phelps County deputies seized property worth millions along Interstate 44 in 2016-2017, but charges were never filed against those drivers

Between 2016 and 2017, police in Phelps County seized more than $2.6 million in cash and other property along a 20-mile stretch of Interstate 44. In Missouri, a state seizure of property requires a criminal conviction. But for the 24 seizures documented on the interstate in that two-year span, seizure reports indiciate zero state charges were filed.

Phelps County’s prosecutor’s office reported estimated value of seizures and valued some items at $0. Image courtesy of St. Louis Public Radio.

Phelps County’s prosecutor’s office reported estimated value of seizures and valued some items at $0. Image courtesy of St. Louis Public Radio.

Law vs. reality

The reality of civil asset forfeiture on Missouri’s highways bears little resemblance to the goals of Missouri law.

Missouri’s law around asset forfeiture says police can’t seize property without a criminal conviction. And when there is a state asset forfeiture, the money goes to public schools.

But that’s not what happens.

Of the $19 million collected in asset forfeitures over the past three years, $340,000 has gone to schools. That’s less than 2 cents on the dollar. Most of the rest of the money went to law-enforcement agencies for new equipment, squad cars, weapons, ammunition and jail cells.

The Phelps County Sheriff’s Department purchased an active shooter simulator, shown in this photograph. The training tool was purchased using money seized through civil asset forfeiture. Image by Brian Munoz. United States, 2019.

The Phelps County Sheriff’s Department purchased an active shooter simulator, shown in this photograph. The training tool was purchased using money seized through civil asset forfeiture. Image by Brian Munoz. United States, 2019.

Instead of a criminal conviction to seize the property, police need only a preponderance of the evidence connecting the cash to drugs. “Preponderance of the evidence” means a claim is more likely true than not true. This is the standard used in civil as opposed to criminal cases.

Preponderance of the evidence requires 50.1 percent of proof. By contrast, a criminal conviction would require proof beyond a reasonable doubt, which some lawyers quantify as about 90 percent.

Often in the Missouri cases, like those in Phelps County, the cash seized is from a motorist who is neither charged with a crime nor caught with drugs.

Hooked on drugs

Missouri law’s high standard of proof is the result of a tough law passed after a six-part series in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1991 titled “Hooked on the Drug Laws.” It documented police abuses in seizing property and then using it for departmental expenses.

Former State Sen. Wayne Goode, D-Normandy, a good-government advocate, shepherded the reform law through the Legislature in 1993. The law directed seized property toward public schools and required a criminal conviction for a state forfeiture.

Michael A. Wolff, counsel to then Gov. Mel Carnahan, remembers a top federal drug official coming to see the governor to urge him to veto Goode’s bill. Afterward, Wolff and Carnahan agreed that vetoing the bill didn’t make sense because the federal drug war wasn’t working anyway. Carnahan signed Goode’s bill.

On paper, the law seems crystal clear. The state constitution states “the clear proceeds of all penalties, forfeiture and fines collected … for any breach of the penal laws of the state … shall be distributed annually to the schools.”

The Goode law also requires a criminal conviction—proof beyond a reasonable doubt—before property can be forfeited to the state.

The off ramp that allows local police and sheriffs to detour around these legal requirements is the federal Equitable Sharing Program. It permits local law-enforcement agencies to turn over their civil asset seizures to the federal government, which then “adopts” them. The feds keep 20 percent for their trouble and return up to 80 percent to the local law-enforcement agencies.

It’s a legal way to wash away the strict state law requirements. The requirements of a criminal conviction and school funding do not apply. Instead, most funds are returned to local police who spend them.

Phelps County stretches roughly from Dixon, Missouri, and Sugar Tree Road in the west, past Doolittle and Rolla to St. James, Missouri. Image by Brian Munoz. United States, 2019.

Phelps County stretches roughly from Dixon, Missouri, and Sugar Tree Road in the west, past Doolittle and Rolla to St. James, Missouri. Image by Brian Munoz. United States, 2019.

Looking for suspicious cars

Court records and interviews with police and lawyers paint a picture of how the process works.

Officers led by Sgt. Carmelo Crivello patrol I-44, watching for suspicious vehicles and then looking for a traffic violations to stop the vehicles—such as changing lanes without a blinker, or touching tires to the rough fog strip on the right of the road.

After the stop, officers separate occupants in the car and question them, looking for discrepancies in their stories. Based on discrepancies, the police ask if there is money or drugs in the vehicle and then ask for consent to search. Most drivers consent. If not, the officers detain the vehicle until a drug-sniffing dog arrives. If the dog indicates the presence of drugs—as it almost always does—police search the vehicle. Critics, such as David B. Smith, a Virginia lawyer, say this amounts to a “charade” because of the unreliability of the dog alerts.

If police believe there is a connection to drug trafficking, they seize the cash even though they don’t have enough proof of a crime to file criminal charges. That’s a far cry from the “beyond-a-reasonable-doubt” standard Missouri law would appear to require.

In the vast majority of the seizures, no state criminal charges are filed, no drugs are seized, and no money goes to public schools. The police keep the cash, and the suspects continue on their way.

Many of the suspects have Spanish names, although the department says it does not use racial profiling. Sixteen of 24 stops during 2016 and 2017 involved drivers with Hispanic names.

The $2 million-plus in cash seized from those stops was sent to the federal government’s Equitable Sharing Program, which then returned most of it for law-enforcement purchases instead of school construction.

Dan Alban, a lawyer for the libertarian Institute for Justice that presses for forfeiture reform, has studied how local law enforcement in Missouri circumvents the state law and how highway interdiction is used to seize people’s property around the country.

“They need reasonable, articulable suspicion to conduct a traffic stop,” he said in an interview. “Once they’ve searched the vehicle—either because they obtained consent or have an alert from a drug dog—they are supposed to identify evidence that any property they seize is connected to a crime. That alleged crime will almost always involve drugs, even if there are no drugs in the car.

“Often, the alleged evidence of criminal activity is based on someone supposedly matching the profile of a drug courier, which can include traveling in a known drug-trafficking corridor, traveling with whatever the police consider to be a large amount of cash, driving a rental vehicle, supposedly inconsistent stories about their trip, bloodshot eyes, nervousness or even air fresheners hanging from the rearview mirror. Unfortunately, (this) is a very low standard for seizures in these traffic stops and can be pretty subjective or even manufactured.”

Phelps County Sheriff Richard L. Lisenbe, himself an expert on highway interdiction, said the asset-forfeiture program hurts organized drug traffickers and is a lifeline for law enforcement.

Forfeiture is “the only thing that keeps our head above water,” he said in an interview. “Most departments don’t have much income … What we use it for is typically training and equipment,” radios, cameras, guns, ammunition. “Before we got in this asset-forfeiture thing, we were driving cars that had 300-400,000 miles on them.”

The sheriff says forfeiture is a “big part” of why the county has a renovated jail. “We saved that money hoping we could do this … This is at no cost to Phelps County whatsoever.”

No drugs, no charges, no money for schools

About $1 million has been returned to Phelps County each year, providing $2.3 million for the new county jail, in addition to more than $100,000 for computers and equipment and $80,000 in salaries in the past two years.

Prosecutor Brendon Fox explained in an interview how the cases work their way through the courts. Fox pointed out that many of the motorists from whom cash is seized on I-44 by Phelps County deputies have not committed a state crime. Driving a car containing a large amount of cash is not a state crime. So stopping a driver with a lot of cash does not lead to a state criminal charge. Therefore, the state requirements on burden of proof and school funding do not apply.

“At my office, the deciding factor is, ‘Do I have a criminal case that links that forfeiture to criminal activity?’ If I do, then frequently, it will be a state-level forfeiture.” But cash alone is not enough for a state drug prosecution, he said.

Even if a small amount of drugs is found, there is unlikely to be a state drug prosecution. “If you find $250,000 and four grams of marijuana, then even though there is an independent criminal case, there isn’t going to be a nexus between four grams of marijuana and a quarter of a million dollars,” Fox said. So no criminal charge is filed.

But that doesn’t mean the property is returned. Instead, the state goes the federal route, with the money returning to the county.

In those cases, the county files a “petition for order of transfer” before a state judge. “The burden of proof (is whether) the cash is more likely or not involved in … criminal activity and the federal government is better equipped” to handle the case, said Fox.

In three-fourths of the civil asset-forfeiture cases filed in Phelps County, there is a petition to transfer to the federal government, records show. Once the state judge approves, the money goes to the federal government, which “adopts” the forfeiture. The federal government approves the transfers partially because Sgt. Crivello, who handles most of the interdictions in Phelps County, is deputized as a federal DEA agent.

Crivello says that even though most motorists he stops are not charged with state crimes and are released, he sometimes gathers information that can help solve bigger drug cases.

Prosecutor Fox’s office gets 5 percent of the money returned from the Feds. The money has enabled him to buy “state-of-the-art wireless. We can take a laptop up to court and automatically connect secure servers at all floors,” he said.

Abuses

Lisenbe and Crivello don’t like to hear of cases where police abuse asset forfeiture by buying margarita machines or expensive sports cars. They remember comedian John Oliver’s 2014 sketch featuring Montgomery County, Texas police buying a margarita machine and Columbia, Missouri Police Chief Ken Burton telling a citizens review board that forfeiture money was “like pennies from heaven … that get you a toy.”

One abuse started in Phelps County before Lisenbe was sheriff. Deputies posted signs warning motorists of a fictitious drug checkpoint ahead, giving them time to get off the highway one exit early at a deserted rural off-ramp. Almost everyone exiting there was guilty. Phelps County would have police cars waiting.

“It was like shooting fish in a barrel,” says Lisenbe. But “people started getting greedy. Indiana was one of them. The police there started shutting down whole highways. The courts came out and said, ‘No, no, no, you can’t do this.”

In a 1998 case, federal Judge James B. Loken of the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in St. Louis expressed his disapproval of the way local law enforcement in Missouri was circumventing state law.

He wrote that the federal government and Missouri state police had “successfully conspired to violate the Missouri Constitution … the Missouri Revised Codes and a Missouri Supreme Court decision.”

Missouri isn’t the only place where law enforcement circumvents state laws. State laws in Indiana, Maine, Maryland, North Carolina, South Dakota, Ohio and Vermont also appear to prevent police from receiving forfeiture revenue. But those states collected almost $200 million in Equitable Sharing revenues returned by the federal government from 2001 to 2013, according to reports. That money, too, goes to law enforcement.

Reform ahead?

Missouri State Rep. Shamed Dogan, R-Ballwin, has tried unsuccessfully during recent legislative sessions to pass a reform measure that would reduce the number of forfeitures that go the federal Equitable Sharing route and thus circumvent state law. Opposition from law-enforcement groups has kept the proposal bottled up in committee.

Dogan is considering two forms of the bill. One would bar officers from sending forfeitures of less than $100,000 to the federal program. An alternative, more palatable to law enforcement, would set the cap at $50,000. In other words, the small seizures would have to comply with state law, while the big seizures could go the federal route. This a common reform in other states.

Ninety percent of the seizures would be under the $100,000 ceiling, and 81 percent below $50,000. So the police incentive to seize cash in those smaller cases would be reduced, because they couldn’t send it through the federal loophole and get it back to spend.

Still, police wouldn’t lose much money for their law-enforcement purposes, because most of the cash is in the biggest seizures. With the $50,000 cap, 80 percent of the cash involved in the seizures could still go the federal route and come back to state law enforcement.

Supporters of the measure hope that a compromise allowing law enforcement to keep the money from the biggest seizures will allow the bill to pass and reduce seizures from those with smaller amounts who are less likely to be involved in the drug trade.

Dogan said in a press statement he wants to eliminate the incentive of police to make the smaller seizures. “The government never produces any drugs, never charges you with a crime, and yet you have to spend more than they have actually seized to get your property back. That’s unfair,” he said.

Meanwhile, the Missouri School Boards’ Association says flatly that the money being spent by local police is school money. It says so in the constitution, the group’s lawyer said. The money would be better spent building new public schools to replace the many buildings that are more than a century old.

![Chelsea-market[1]](https://forfeitureusa.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Chelsea-market1-180x180.jpg)